supervised learning methods include among others, neural networks, which will be the primary category of methods which are included for now. They are neutral as to the interpretation

At the broadest sense, supervised learning methods maps structured information to structured information. In so doing, it also forms a representation of the thing in itself.

You’ve heard by now that machine learning refers to a broad set of techniques which allow computers to learn from data. But learn what exactly, and how? Let’s consider several concrete examples in which techniques from machine learning can be applied.

Example 1: Suppose you are a climatologist who is trying to devise a computer program which can predict whether or not it will rain on a given day. Turns out this is hard! But intuitively we understand that rain has something to do with the temperature, atmospheric pressure, humidity, wind, cloud cover, location and time of year, and so on.

Example 2: Gmail, Yahoo, and other e-mail services provide tools to automatically filter out spam e-mails before they reach your inbox. Like in the rain example, we have a few intuitions about this task. E-mails containing phrases like “make $$$ now” or “free weight loss pills” are probably suspicious, and we can surely think up a few more. Of course the presence of one suspicious term does not guarantee it’s spam, and so we can't take the naive approach of labeling spam for any e-mail containing any suspicious phrase.

The way a traditional programmer might go about solving these problems is to carefully design a series of rules or conditional statements which are tested at runtime to determine the result. In the spam example, this could take the form of a decision tree: upon receiving an e-mail, check to see if it’s from an unknown sender; if it is, check to see if the phrase “lose weight now!” appears, and if it does appear and there is a link to an unknown website, classify it as spam. Our decision tree would be much larger and more complicated than this, but it would still be characterized by a sequence of if-then statements leading to a decision.

Such a strategy, commonly called a “rule-based” or “expert system,” suffers from two major weaknesses. First, it requires a great deal of expert guidance and hand-engineering which may be time-consuming and costly. Furthermore, spam trigger words and global climate patterns change continuously, and we'd have to reprogram them every so often for them to remain effective. Secondly, a rule-based approach does not generalize. Notice our spam decision tree won’t adapt to predicting the rain, or vice-versa, nor will they easily apply to other problems we haven’t talked about. Expert systems like these are domain-specific, and if our task changes even slightly, our carefully crafted algorithm must be reconstructed from scratch.

Learning from past observations

With machine learning, we take a different approach. We start by reducing these two very different example problems given above to essentially the same generic task: given a set of observations about something, make a decision, or classification. Rain or no rain; spam or not spam. In other problem domains we may have more than two choices. Or we may have one continuous value to predict, e.g. how much it will rain. In this last case, we call this problem regression.

In both of our two examples, we have posed a single abstract problem: determine the relationship between our observations or data, and our desired task. This can take the form of a function or model which takes in our observations, and calculates a decision from them. The model is determined from experience, by giving it a set of known pairs of observations and decisions. Once we have the model, we can make predicted outputs. [this is all sloppy, fix this]

[Known observations] -> [Learning] <- [Known outputs] || [Unknown observation] -> [ Model ] -> Predicted output

Machine learning also takes the position that such a functional relationship can be learned from past observations and their known outputs. For the rain prediction problem, we may have a database with thousands of examples where those variables we think are important (pressure, temperature, etc) were measured and we know whether or not it actually rained those days. In the spam example, we may have a database of e-mails which were labeled as spam or not spam by a human. Using this data, we can craft a function which is able to modify its own internal structure in response to new observations, so as to be able to improve its ability to accurately perform the task. Formally, the set of previous examples with its known outcomes is often called a ground truth and it is used as a training set to train our predictive algorithm. [[ all of this needs to be fixed/merged with previous section ]]

More generally, what's been defined in this section is called supervised learning and is one of the foundational branches of machine learning. Unsupervised learning refers to tasks involving data which is unlabeled, and reinforcement learning is a hybrid of the two, but we will get to those later.

data-driven ?

The simplest machine learning algorithm: a linear classifier

We've introduced the notion of an algorithm which which makes a series of empirical observations about something and uses those observations to make a decision about something.

Now we will now make our first predictive model, a simple linear classifier. A linear classifier is defined as a function of our data, \(X\), and

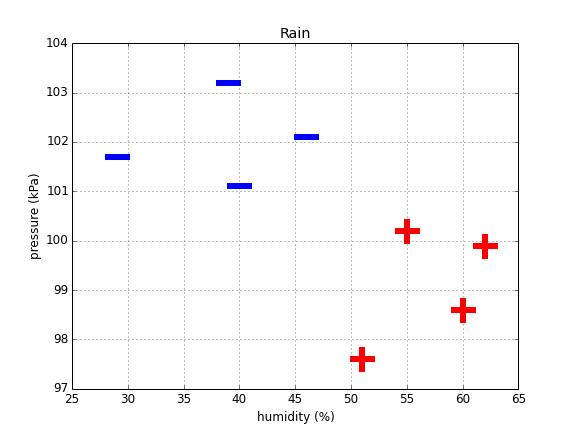

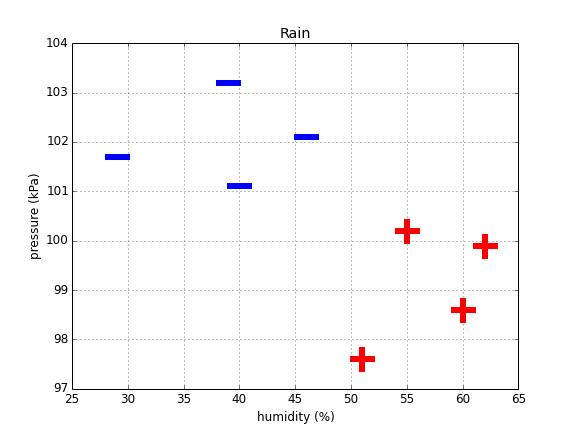

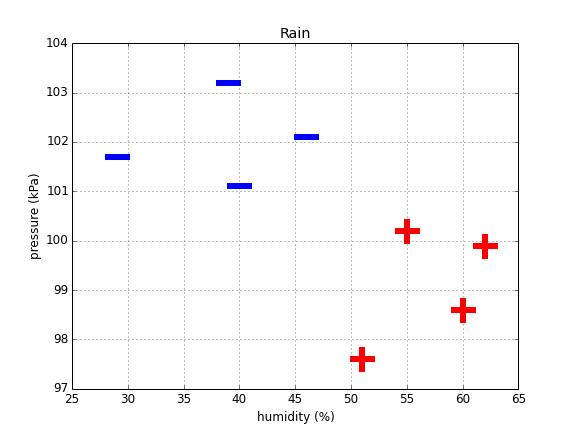

Let's take our first example, that of predicting whether or not it will rain on a given day. We will use a simplified dataset which consists of only two observations: atmospheric pressure and humidity. Suppose we have a dataset with 6 days of past data.

- notes

- make two columns, put humidity + pressure into

| Humidity (%) | Pressure (kPa) | Rain? |

| 29 | 101.7 | - |

| 60 | 98.6 | + |

| 40 | 101.1 | - |

| 62 | 99.9 | + |

| 39 | 103.2 | - |

| 51 | 97.6 | + |

| 46 | 102.1 | - |

| 55 | 100.2 | + |

Let's plot these on a 2d graph.

Intuitively, we see that rainy days tend to have low pressure and high humidity, and non-rainy days are the opposite. If we look at the graph, we can see that we can easily separate the two classes with a line.

If we let \(x_1\) represent the humidity, and \(x_2\) represent the pressure, we can plot a line on our graph with the following equation:

\[w_1*x_1 + w_2*x_2 + b = 0\]where \(w_1\), \(w_2\), and \(b\) are coefficients that we can freely choose. If we set \(w_1 = 5\), \(w_2 = 6\), and \(b = 1.2\), and then plot the resulting line on the graph, we see it perfectly separates our two classes. We call this line our decision boundary.

(equation should be written beside the line, Ax+By+C)

Suppose we know today's humidity and pressure, and are asked to predict whether it will rain or not. Let's say we are given \(x_1 = 20\) and \(x_2 = 3\). We can plot this new point on our graph.

(now with new point, as a ?)

It appears on the negative side of our decision boundary, and thus we predict it won't rain. More concretely, our classification decision can be expressed as:

\[\begin{eqnarray} \mbox{classification} & = & \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1 & \mbox{if } w_1*x_1 + w_2*x_2 + b \gt 0 \\ 0 & \mbox{if } w_1*x_1 + w_2*x_2 + b \leq 0 \end{array} \right. \tag{1}\end{eqnarray}\]This is a 2-dimensional linear classifier.

Now let’s do the same thing in 3 dimensions. add a column. we get this:

A flat plane in 3d is analogous to a line in 2d, and is thus called "linear." This is true in general for any n-dimensional hyperplane. Linear classifiers are limited because in reality, most problems that interest us don’t have such flat behavior; different variables interact in various ways.

Dimension X

In practive, we have many many dimensions, but it works the same.

Limitations of linear classifier

sometimes our data is not linearly separable. Suppose we receive a training set that looks like this: dots in the middle.

Clearly, no line is going to

[ 3 ] - 2d non-linearly separable

no labels

Later, unsupervised

Connecting the dots

It may seem hard to believe, but this simple setup forms the core of

the same linear classifier which is simply telling apart two objects from each other are the thing that underpins puppy slugs, shakespeare bots, word embeddings (word2vec), and others. this may seem hard to believe at first but it rests on a subtle point. When we train an algorithm to discern the relationship between a set of observations and a corresponding behavior, we are doing more than letting it make new predictions. We are also forming a representation of our subject of interest, a computational schematic

** taken together, the weights and the biases are often also called parameters because the behavior of our machine depends on how we set them.

Supervised learning

this is supervised elarning. used for blah

Regression: simple example

To make things more concrete, let’s take a look at the simplest example of machine learning: linear regression. If you have ever taken a high school statistics course, you have probably solved these by hand!

Linear regression is a technique used to discover the underlying functional relationship between

Linear regression in 2d Linear regression in 2d (p5?)

Variations

- logistic regression/classification

In practice, linear regression is almost never used because most of the functions we care about are not so simple, and more complex methods are required.

- bishop

- overfitting

Unsupervised learning

Find underlying structure

Reinforcement learning

physics demo (balancing a stick) (top banner?). this book will prbbably mostly reference

from: http://ufldl.stanford.edu/tutorial/supervised/LinearRegression/

For example, we might want to make predictions about the price of a house so that represents the price of the house in dollars and the elements of represent “features” that describe the house (such as its size and the number of bedrooms). Suppose that we are given many examples of houses where the features for the i’th house are denoted and the price is . For short, we will denote the

Our goal is to find a function succeed in finding a function prices, we hope that the function given the features for a new house where the price is not known. so that we have for each training example. If we like this, and we have seen enough examples of houses and their will also be a good predictor of the house price even when we are given the features for a new house where the price is not known.

We initialize a sigmoid neural network with 3 input neurons and 1 output neuron, and 1 hidden layer with 2 neurons. Every connection has a random initial weight, and neurons in the hidden and output layers have a random bias.